Understanding High Dimensional Tensor Multiplication

Exploring AI Mechanistic Interpretability with For Loops

Recently, I have been learning about AI Mechanistic Interpretability. These AI tools, like ChatGPT, feel almost magical, and I can’t help but wonder how they really work. Over the years, I have learned that technology isn’t usually safe by default. I believe understanding a system fully is often the best way to guarantee its safety and security, a belief shaped by my experiences. If we’re deploying AI models across industries at scale, we should probably understand not just their outputs, but also the inner workings. It’s like looking under the hood to see what makes the engine purr before we put it on the racetrack.

Understanding Transformer Calculations

When I started implementing transformers, I was often faced with high dimensional tensor calculations like this:

\(W\) has shape \([num_{attnheads}, d_{model}, d_{head}]\)

Residual stream \(x\) has shape \([batch, sequence, d_{model}]\)

\(Q = Wx + b\) has shape \([batch, sequence, num_{attnheads}, d_{head}]\)

At first glance, these high-dimensional tensor operations seemed pretty confusing. But after weeks of chipping away at it, I found something clicked: there’s actually an intuitive way to think about these calculations - using the concept of “for loops.”

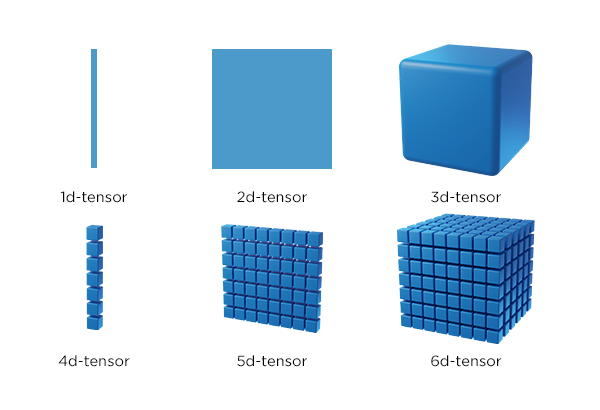

Figure: Tensors with different dimensions

Breaking Down the Residual Stream \(x\)

In the case of transformers, the residual stream is our incoming data. For simplicity, let’s say each token in the data is a word—like “ am”. As input, each token is represented by a vector of numbers, and the length of that vector is called “d_model.” From there, all the other dimensions in the tensor are basically loops, repeating this transformation step by step. You could imagine breaking down the calculation for \(Q = Wx + b\) as the following psuedo code:

For each batch of data (e.g., a paragraph):

For each sequence of tokens in the batch (e.g., a sentence):

For each token (e.g., a word):

Perform some operation on the token vector.

And that’s essentially what’s happening with \(x\)!

Understanding the Weight Matrix \(W\)

Now, let’s look at \(W\). This part can feel more complex, but the for loop analogy still works. \(W\) is fundamentally a linear transformation that maps vectors of size \(d_{model}\) to vectors of size \(d_{head}\), doing this for each attention head. The equation \(Q = Wx + b\) can be imagined like this:

For each batch of data (e.g., a paragraph):

For each sequence of tokens in the batch (e.g., a sentence):

For each token embedding vector in the sequence (e.g., a word):

For each attention head:

Map the vector x_vector (size d_model) to a vector of size d_head.

The result of this is that \(Q\) ends up with a shape of \([batch, sequence, num_{attnheads}, d_{head}]\). Using this nested “for loop” structure helps me keep the dimensions and relationships clear in my head. Underneath it all, we’re really doing a simple linear transformation, but we’re doing it many, many times.

Why Use Tensors Instead of For Loops?

Well, GPUs are incredibly efficient at computing products of high-dimensional tensors in parallel. For loops imply sequential calculations, which can be painfully slow. Considering we need to perform tons of matrix operations in each iteration of training—and do it for many iterations—using tensors is definitely the way to go. But conceptually, thinking in terms of nested loops helps me distinguish between the tensors that are manipulating data versus those that represent data or weights in the model.

Summary: For Loops as a Mental Model

So, in short, using “for loops” as a mental model can make these complex tensor operations more approachable—a bridge from traditional procedural programming into the tensor world. It has helped me not only understand the transformer algorithm but also check if my outputs have the right shape. I’ve heard it’s common for ML engineers to spend nontrivial amount of time lining up shapes of tensors!

Using this Mental Model to interpret features in LLMs

Next up, I’ll show how this “for loop” approach can also be useful for interpreting features in sparse autoencoders. Stay tuned!